Listen to this podcast on your favorite platform with the podcast app above

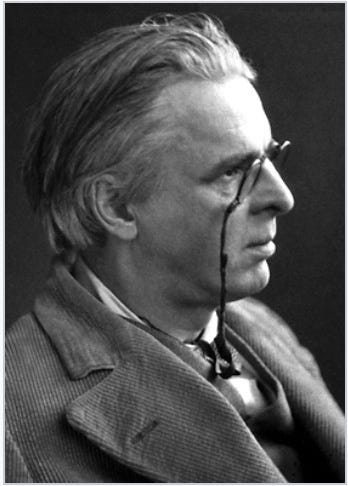

In his famous poem, Yeats goes on about sailing the seas to ‘the holy city of Byzantium’. Once there he proposes to escape the bonds of mortality and find new life as some sort of a magical bird ‘set upon a golden bough to sing’.

That’s how I read it anyways with a little help from Andrew Spacey.

Byzantium of course was the ancient capital of the Byzantine Empire, the center of European culture for a thousand years after the fall of Rome. It was his dream city, a magical place in his mind.

And of course human beings have been sailing the seas looking for their dream place since forever, since people crossed the water from Asia to the Australian subcontinent some 60,000 years ago. Nobody knows how they did it, there is no evidence of sailing or boats or traversing oceans before then but somehow they managed to cross hundreds of miles of open water and suddenly found themselves in Australia. Quite an adventure. The first sea voyage of discovery.

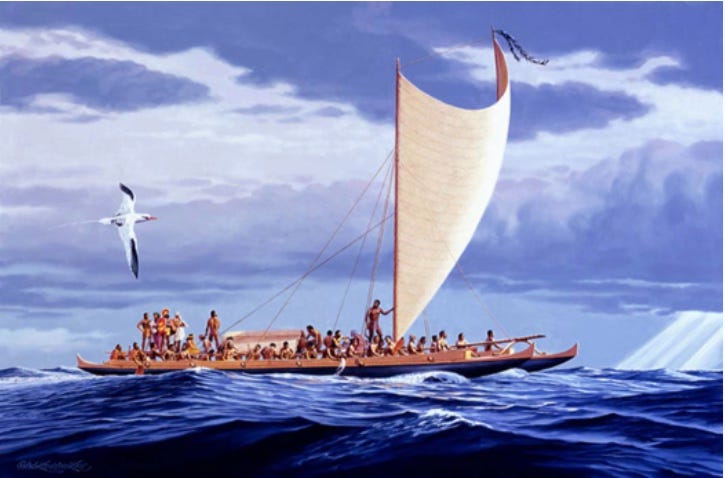

The ancient South Pacific Islanders used to voyage across immense spans of ocean in their 50 foot long double hulled canoes thousands of years ago. Using navigation techniques that defy modern day understanding they were able to sail from Tahiti to Hawaii and to nearly every island within the vast Polynesian Triangle using knowledge of the stars, of the birds and the ocean swells, of the wind patterns, the clouds and the color of the sky, information which they gleaned from a large body of knowledge they had accumulated and stored in their oral traditions. They would literally sing themselves from island to island as they recalled the knowledge of their ancestors.

They first moved east from New Guinea around 1500 B.C, into the vast ocean world and colonized the Solomon Islands, then the Banks and Vanuatu Archipelagos. As islands grew farther and farther apart, their navigational skills grew more sophisticated. From tens of miles at the edge of the western Pacific to hundreds of miles along the way to Polynesia, to thousands of miles for the voyages to Hawaii and Easter Island.

Imagine arriving on a Pacific atoll after spending weeks or maybe months on the rolling waves and then disembarking on a pristine new world that no humans had ever seen before.

The 18th and 19th century French Canadians who transported furs from the interior of the vast Canadian forests down the wild rivers in their 30 foot canoes were having adventures too. They were called ‘voyageurs’ and were usually 10 to 12 hardy men in a boat, singing away to keep the tempo, paddling 12-14 hours a day hardly missing a beat, stopping only long enough to smoke a bowl with their long stemmed pipes each hour, camping out along the banks of the river until they arrived at the trading post on the edge of the frontier.

It was considered a romantic and adventurous lifestyle, in the folklore and music of the time. A rowdy band of boisterous boys singing bawdy songs and paddling along the winding rivers with tall trees on either side, watching out for rapids and unfriendly Indians? What a deal! There was the promise of celebrity and wealth, but much like the gold diggers in California and Alaska, it was mostly a massive amount of hard work and the privations of a primitive lifestyle.

Paddling downstream on a warm sunny day with a canoe full of beaver pelts with your buddies was one thing, portaging rapids carrying two ninety pound bundles was quite another. And then there’s the canoe.

The voyageurs would travel deep into the interior to trade with the First Nations people. The deeper they went, the better the price. Steel hatchets, kettles, broadcloth, guns, liquor and other items of European manufacture were exchanged for pelts of marten, otter, lynx, mink and beaver. Sometimes they would over-winter in the vast boreal forests of Canada before they returned using skills they had learned from the First Nations people.

It was a cruel and wanton business that almost exterminated some of those fur bearing species, but it was also one of ways that the vast hinterland was explored and developed not only in Canada but in Siberia as well. Gotta keep warm in the 17th Century before coal and efficient furnaces became widely available to warm people’s homes.

And so the voyageurs were off, come spring and the ice cleared from the rivers, to points west and north of Montreal. They were bound for glory and riches, or at least some wild adventures.

Although not much is known about the boats used by the Incas to traverse the west coast of South America, this drawing from a book published in 1748, resembles the description given by 16th century Spanish explorers of the raft-like boats they encountered there.

The description goes like this.

[The Spanish] captured a ship [raft] with as many as 20 men aboard of whom 11 threw themselves into the water. [Ruiz] put the remainder of the crew onshore except for three whom he kept as interpreters. He treated them well. The ship he took had a capacity of up to 30 toneles [25 metric tons]. The keel was made of canes [balsa logs] as thick as posts bound together with ropes of what they call henequen, which is like hemp. it had an upper deck made of lighter canes, tied with the same kind of ropes. The people and their cargo remained dry on the upper deck, as the lower logs were awash in the sea water. The ship had masts of good wood and lateen-rigged sails of cotton, the same as our ships, and good rigging with henequen ropes. It carried stone weights like barber's grinding stones as anchors.

Apparently they traded all up and down the coast as far as Mexico in their raft boats. That must have been some adventures too.

Thor Heyerdahl in 1947 floated or sailed 4,300 miles across the Pacific Ocean from Peru to the Polynesian Islands on his balsa wood raft, the Kon-Tiki, built in the native style using native materials. It took him 101 days and proved the point that the ancient Inca could have made long sea voyages with their boats.

Whether they did or not, is unknown. Heyerdahl and his mates did though, on the Kon Tiki, a name that refers to the powerful Inca creator god Viracocha, who oversaw the Inca culture from the very beginning of time.

Viracocha was the maker of all things and the substance from which all things were made. He made the sun, the moon, and the stars. He made mankind by breathing into stones. He was intimately connected to the sea and eventually disappeared by walking across the Pacific Ocean never to return. In the myths of the Inca he wandered the earth disguised as a beggar, teaching the basics of civilization to his creation everywhere and working miracles. Of course.

The Vikings knew how to sail some ships. They crossed the Atlantic ocean in their longships and discovered Newfoundland in 1021, way before Columbus floated into the Caribbean; they just didn’t have the same flare for franchise development. They were mainly farmers but they would have gnarly adventures from time to time just for the heck of it and raid England or sail up the Seine and sack Paris.

And European boats, of course, we are all familiar with. The caravels of Columbus, the Pilgrims 3 masted galleon, the Mayflower. Magellan and his fleet of carracks circumnavigating the whole round world without falling off. Well only one of them made it all the way around, 30 men out of the 270 member original crew survived. Might have been a little too much adventure

People have been traversing the earth, exploring and discovering and unfortunately conquering and subjugating for a very long time.

We’re all on a journey is the point of my sermon, some kind of a journey, across some kind of an ocean, to some kind of a destination. The beautiful reward as Bruce Springsteen put it or like old William Butler Yeats sailing to the holy city of Byzantium. He wanted to become a bird singing to the lords and ladies of Byzantium from a golden bough. I’m not sure why. Maybe that was the best image he could come up with to counter his concerns of growing old and dying. Substitute heaven or reincarnation or the Elysian Fields for the virtuous Greek souls or Valhalla for the courageous Viking warriors.

Maybe it’s as we imagine it to be. A wild ride and a glorious adventure. That would be mine. Maybe this is just for practice, each little journey of our day I mean. Hey there’s a thought.

Sailing to Byzantium

I

That is no country for old men. The young

In one another's arms, birds in the trees,

—Those dying generations—at their song,

The salmon-falls, the mackerel-crowded seas,

Fish, flesh, or fowl, commend all summer long

Whatever is begotten, born, and dies.

Caught in that sensual music all neglect

Monuments of unageing intellect.

II

An aged man is but a paltry thing,

A tattered coat upon a stick, unless

Soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing

For every tatter in its mortal dress,

Nor is there singing school but studying

Monuments of its own magnificence;

And therefore I have sailed the seas and come

To the holy city of Byzantium.

III

O sages standing in God's holy fire

As in the gold mosaic of a wall,

Come from the holy fire, perne in a gyre,

And be the singing-masters of my soul.

Consume my heart away; sick with desire

And fastened to a dying animal

It knows not what it is; and gather me

Into the artifice of eternity.

IV

Once out of nature I shall never take

My bodily form from any natural thing,

But such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make

Of hammered gold and gold enamelling

To keep a drowsy Emperor awake;

Or set upon a golden bough to sing

To lords and ladies of Byzantium

Of what is past, or passing, or to come.

W. B. Yeats, “Sailing to Byzantium” from The Collected Poems of W. B. Yeats (1989)

music from Cafe de Anatolia

Share this post