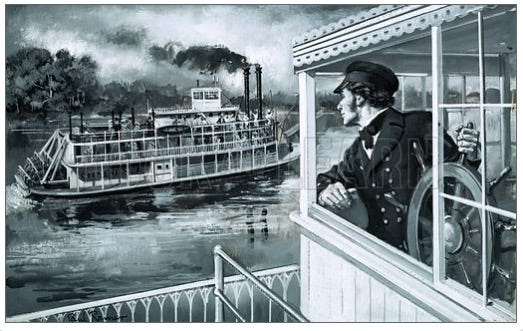

The river changes daily, according to Mark Twain in his book Life on the Mississippi. He relates, in a slow, deliberate way, his adventures piloting a steamboat up and down the great river from St. Louis to New Orleans. How the slow muddy water surges and peaks, flows low in the dry season. All the subtle intonations, all the messages in the ripples and in the flat water. Every day something new and unexpected appears, trees floating down the middle of the river and how it twists and turns like a corded knot finding new beds to lie in leaving behind oxbows and resacas and islands in the stream. Twain makes the point urgently and often - a steamboat pilot must know all these things.

And so it is with Broadway, my Mississippi River. It runs straight down the valley of San Antonio and in fact used to be part of the river bed itself. The stream of cars courses and winds its way thru the street. It has ebb and flow - the lunch rush and the commuter traffic jam. It can change direction and find a new way, just like the big river, when the light changes. Best to stay out of the rapids for that - let it run its course, hug the shore, take the sidewalk, heck maybe even a bike lane if you’re lucky.

The other day I almost got run over by a cop car. He decided to back up when the light changed and I was right behind him. Did not expect that. Sometimes at intersections there are cars turning, cars running the amber light, cars waiting - all potentially dangerous and like Mark Twain navigating the big river I have to make my way with all due caution and care. Don’t want to end up run over and squashed in the street.

Yelling was a sport and a necessity on the wide Mississippi - cautioning the flat boats and the log rafts and the barges. So it is on my bike cruising down Broadway. A good Comanche yell once in a while improves your health, I believe, and also advises the motorists not to drift too far off course.

Everything has its rise and fall. Don’t you know it and the bicycle pedals, like the old paddle wheels, go round and round.

Weather is to be accounted for too riding thru the valley of San Antonio or anywhere for that matter. A woman in the cafe once told me her story of being thrown off her bike and into the curb by a car that didn’t see her. She was caught in the glare of a low sun. “Were you ok?” I asked. “Sure, I got up and walked it off” she said, “I’m a yoga girl.”

Well there’s two lessons - stay out of sun glare and do your yoga.

Then there’s downstream and upstream. The old steamboats could only make about 5 miles per hour up stream but going back down could get up to 10 or 12 mph with the boiler steaming away full blast, nigh on to bursting. It was dangerous business though, during the mid 19th century 289 steamboats sank on the Mississippi River killing over 4,000 people. If it wasn’t snags ripping open the bottom of the boat it was the boiler exploding sending up a shower of steel and wood where the boat had been a moment before.

On my river a prevailing wind comes from the southeast off the Gulf of Mexico 150 miles away. I can tell before I get out of bed what kind of weather is out there - the airplanes take off into the wind and come right over my head when the wind is out of the southeast. You can bet on those brilliant mornings when the wind is out of the north and it’s all downhill and down wind all the way to downtown. I can ride hard with hardly an effort, way faster than a steamer, 17, 18, 20 mph passing buses and yelling at cars stuck at the light or slowly creeping up to one.

There are different laws for bikes than there are for cars, they understand that. And the motorists admire a skilled bicyclist who can slip thru the lights with barely a brake fade, fan tail blinking and head down to make way with minimum resistance.

The other day a black and white cop car passed me four times, back and forth on Broadway. He was trying to catch me. Probably heard rumors of the mad anarchist bicycle rider ignoring all the laws of the land flying up and down B’way. He didn’t know this is my street. I play the percentages and make sure they’re well in my favor. I don’t mind going slow. I don’t mind stopping at lights for the sake of the cop stopped on the other side. He never did catch me.

Not being arrogant, just truthful. Cars have to maintain their distance, they’re big and heavy. Not bikes, they’re lithe and slender and can scoot thru the narrowest chute. Mark Twain would appreciate that. He describes the science of reading the river and finding the most efficient route around the bends and over the sand bars while staying close to shore, if possible, where the current is lax. It’s the same with bike riding.

Sunday mornings are the best, or in the midst of a world-wide pandemic. Then the streets are clear and open to any speed. If you can attain it and hold it, 25 mph is not unheard of on such mornings with a stout northerly breeze. All the more focused is the bicycle rider in such circumstances, again not unlike the steamboat pilot a-full tilt downstream avoiding all possible dangers and tragedies before they arrive.

What a pleasant surprise to discover Mark Twain on my ride. His pseudonym, by the way, Mark Twain, was yelled out by the lead man at the front of the boat and indicated two fathoms or 12 feet of water measured with a pole. That was enough for safe passage. The old steamboats were designed with a shallow draft, 4 or 5 feet, for that purpose precisely. Not fast or agile though, unlike a bike.

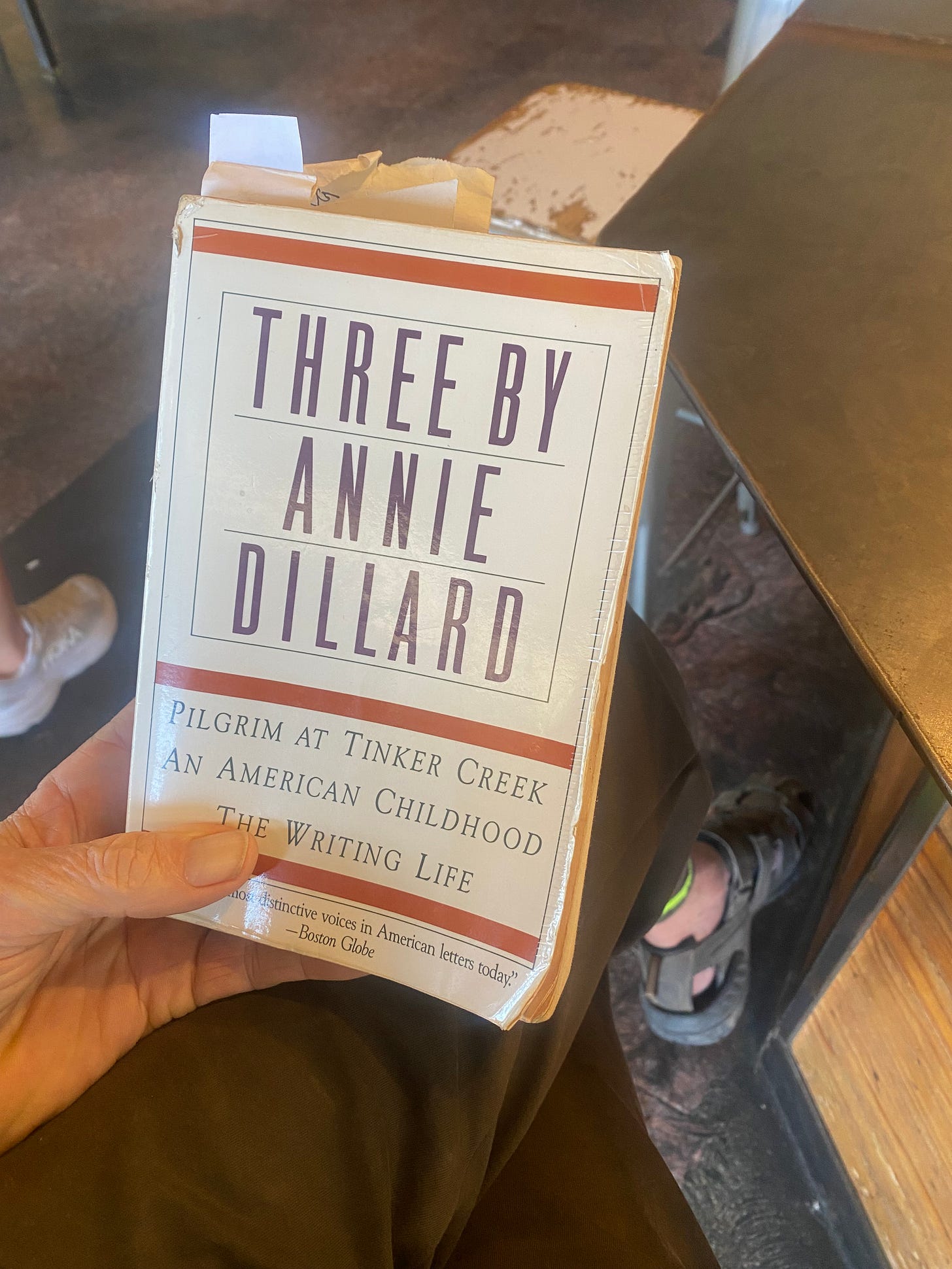

At the same time I’m reading Annie Dillard An American Life. It’s her memoir of growing up in Pittsburgh during the fifties (1950’s). Her stories are eloquent and hilarious. I’ve read it twice and once more, it’s filled with bookmarks - sales receipts slips of paper and a napkin. The cover shows three generations of generous wear.

“Richland Lane was untrafficked, hushed, planted in great shade trees, and peopled by wonderful collected children. They were sober, sane, quiet kids, whose older brothers and sisters were away at boarding school or college. Every warm night we played organized games—games that were the sweetest part of those sweet years, that long suspended interval between terror and anger.”

She chronicles the terror by means of her inventive stories. Although she was friends with the Catholic kids in her neighborhood, she was frightened by the nuns. Her family (and her lineage) were Protestant and the Catholics were perceived with some suspicion. They had strange rituals, went to mass and listened to the pope. They sprinkled babies.

“Now St. Bede’s was, as the expression had it, letting out; Jo Ann Sheehy would walk by again, and all the other Catholic children, and perhaps the nuns. I kept an eye out for the nuns.

From my swing seat I saw the girls appear in bunches. There came Jo Ann Sheehy up the dry sidewalk with two other girls; her black hair fell over her blue blazer’s back. Behind them, running back and forth across the street, little boys were throwing gravel bits. The boys held their workbooks tightly. Probably, if they lost them, they would be put to death.

In the leafy distance up Edgerton I could see a black phalanx. It blocked the sidewalk; it rolled footlessly forward like a tank. The nuns were coming. They had no bodies, and imitation faces. I quitted the swing and banged through the back door and ran in to Mother in the kitchen.

I didn’t know the nuns taught the children; the Catholic children certainly avoided them on the streets, almost as much as I did. The nuns seemed to be kept in St. Bede’s as in a prison, where their faces had rotted away—or they lived eyeless in the dark by choice, like bats. Parts of them were manufactured. Other parts were made of mushrooms.”

Good grief, what perceptions of a child, knowing so little of the world but aware and receptive to her own interpretations. A world wondrous but in equal parts frightening. No guardrail yet between imagination and reality.

“In the kitchen, Mother said it was time I got over this. She took me by the hand and hauled me back outside; we crossed the street and caught up with the nuns. ‘Excuse me,’ Mother said to the black phalanx. It wheeled around. ‘Would you just please say hello to my daughter here? If you could just let her see your faces.’

I saw the white, conical billboards they had as mock-up heads; I couldn’t avoid seeing them, those white boards like pillories with circles cut out and some bunched human flesh pressed like raw pie crust into the holes. Like mushrooms and engines, they didn’t have hands. There was only that disconnected saucerful of whitened human flesh at their tops. The rest, concealed by a chassis of soft cloth over hard cloth, was cylinders, drive shafts, clean wiring and wheels.

‘Why, hello,‘ some of the top parts said distinctly. They teetered toward me. I was delivered to my enemies and had no place to hide; I could only wail for my young life so unpityingly snuffed.”

The whole book is 282 pages of finely wrought details and nuanced descriptions. Story after story in all its narrative glory, exquisitely rendered. What I learned is that her childhood was nothing like mine (except for the Catholic part). For one, I remember so little that I sometimes wonder if I even had a childhood and two what I do remember was exceedingly and invariably tedious and boring. Hers was full of colorful adventure and excitement, as she tells it.

If she was not playing detective and spying on suspicious neighbors or at dancing school learning about boys or exploring the neighborhood on her bicycle (I did that) she was collecting rocks and inventorying them or investigating pond water with her microscope or playing capture the flag in the street. Her father was fascinated with Mark Twain’s account of the river - that’s where I got the idea to read Life on the Mississippi and at one point got in his boat and attempted to sail to New Orleans. My father was the minister of a small Baptist church and didn’t have a boat but we did have a very nice 1963 Impala. Her account of playing football with the boys is priceless.

“Some boys taught me to play football. This was fine sport. You thought up a new strategy for every play and whispered it to the others. You went out for a pass fooling everyone. Best, you got to throw yourself mightily at someone’s running legs. Either you brought him down or you hit the ground flat out on your chin, with your arms empty before you. It was all or nothing. If you hesitated in fear, you would miss and get hurt: you would take a hard fall while the kid got away, or you would get kicked in the face while the kid got away. But if you flung yourself wholeheartedly at the back of his knees—if you gathered and joined body and soul and pointed them diving fearlessly—then you likely wouldn’t get hurt, and you’d stop the ball. Your fate, and your team’s score depended on your concentration and courage. Nothing girls did could compare with it.”

Yeah she had a stimulating childhood, but you work with what you’ve got. That’s the other thing I learned. She spent many hours reading books of all sorts, from the public library and from her parents. I spent endless hours in church, one sort of church or the other, and striving to go to heaven by not doing anything that was the least bit daring or, God forbid, fun.

The account she gives of her parent’s sense of humor struck a chord. I saw a resemblance there for my mother loved to tell jokes and elicit laughter too. I’ve carried on the tradition. I clearly remember our mother’s favorite joke and so does, I’m sure, all of us kids. She would tell it at every important function, whenever enough of an audience was present to make it worth the telling.

There were three sisters (or was it friends), anyways, as I recall it there was the flapper girl (an expression from the 1920’s that basically means a flirtatious woman), there was the common ordinary girl (run of the mill working class) and there was the plain girl. Probably cleaned houses or something.

So they’re all going out on dates, it’s Saturday night, and they agree that in the morning when they meet for breakfast (I guess they were sisters or maybe they were in a boarding house) they would say good morning as many times as they got kissed the night before. Kind of a secret code, subliminal conversation going on, maybe under the nose of the disapproving mother. My exegesis here, not part of the joke.

So the next morning the flapper girl comes in and says ‘Good morning. It’s a good morninng this morning. If it’s as good of a morning tomorrow morning as it is this morning it’ll be a good morning tomorrow morning. The common girl comes in and says ‘Good morning.’. The plain girl comes in and says, “Howdy, darn it”.

That was a hilarious joke back in the day. A Bayes family favorite. What was most amusing was witnessing my mother’s delight in telling it as if it were the first time we had all heard ‘the old maid joke’. She told it straight ahead, smiling the whole way with her wide smile, barely able to contain her mirth anticipating the punch line which we all knew was coming. It never changed. It didn’t need to.

If you would like to support the rohn report, please consider becoming a paid subscriber

or make a one time donation. It’s deeply appreciated. Thank you.